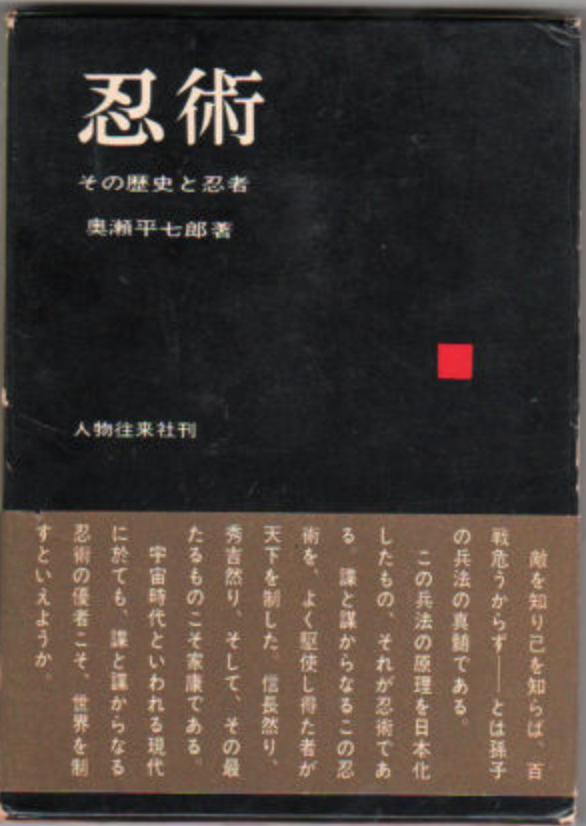

Excerpt about Ninja History from the book Ninjutsu Sono Rekishi To Ninja by Heishichirō Okuse.

Ancient Ninjutsu (600-700)

The Beginnings of Ninjutsu: A Chinese Origin. Ninjutsu did not originate in Japan. Between the 6th and 7th centuries, the knowledge of Chinese military strategy, specifically the “Art of Espionage” (Yōkan-jutsu) from Sun Tzu’s The Art of War (Sunzi), was imported into Japan. This became the “seed of ninjutsu,” which, over many centuries, evolved during the Warring States period (15th–16th centuries) into Japan’s unique “ninjutsu,” distinct from military strategy (Heihō) and martial arts (Bujutsu). This section, therefore, naturally focuses on tracing when, by whom, and how this “seed of ninjutsu”—the Yōkan-jutsu from Sunzi—was brought to Japan and put into practical use. The five chapters of this section all address this central theme.

Ninjutsu in the Nara Period (710-794)

The Nara period (710–794 CE) was a time when Japan’s ancient indigenous culture (Shinto culture) and the newly imported Chinese culture (Buddhist culture) intermingled and began to integrate. Due to the necessities of religious conflicts, the Chinese military strategy of espionage (Yōkan), inherited from previous eras, was further developed by Shugendō practitioners (mountain ascetics) into what became known as Yamabushi Heihō (Yamabushi Military Strategy). This development is a significant event in the formation of ninjutsu and must be thoroughly explored. Additionally, the introduction of esoteric Buddhism (Mikkyō) and the propagation of Buddhist teachings (Fukyō), which strongly influenced this process, are indispensable elements in the formation of Yamabushi Heihō that cannot be overlooked. This chapter focuses on tracing the historical successors of The Art of War (Sunzi)’s military strategy (espionage), examining the Shugendō tradition and its founder, En no Gyōja, and exploring how esoteric Buddhism, ancient Shinto, and Sunzi’s military strategies were blended in the hands of Yamabushi ascetics, evolving into something new.

Ninjutsu in the Heian Period (794-1185)

The “seed of ninjutsu,” known as Yamabushi Heihō (Yamabushi Military Strategy), spread across Japan during the Heian period (794–1185 CE) as it absorbed Yin-Yang philosophy (Onmyōdō) and expanded alongside the growth of esoteric Buddhism (Mikkyō), marked by the construction of Mikkyō temples nationwide. As these temples began employing warrior monks (Sōhei) to protect and develop their estates, Yamabushi Heihō spread from the Yamabushi to the warrior monks. Over time, interactions between warrior monks and samurai (Bushi) emerged, resulting in the transmission of Yamabushi Heihō techniques to the samurai class. This phenomenon was not limited to specific regions but became a nationwide trend. Notably, the rising Genpei clans—particularly the Genji (Minamoto clan)—developed a special relationship with Yamabushi Heihō. This section focuses on these historical developments, examining how figures such as Yin-Yang masters (Onmyōji), Genji warriors, Fujiwara Chikata, Kōga Saburō, the Hattori clan, and Heian-period bandits mastered Yamabushi Heihō, emerging as early inheritors of these techniques. Readers should pay particular attention to the frequent appearance of individuals from Iga and Kōga in these phenomena, as this highlights their significant role in the early development of ninjutsu.

Ninjutsu in the Genpei Period (1180-1185)

By the end of the Heian period (794–1185 CE), with signs of nationwide turmoil emerging, Yamabushi Heihō (Yamabushi Military Strategy) reached a stage of completion. This is exemplified by the Kurama Eight Styles (Kurama Hachiryū), a system in which military strategy (Heihō), martial arts (Bujutsu), and ninjutsu (Ninjutsu) were still grasped as a unified whole, not fully independent, but internally beginning to diverge into specialized fields. Through the efforts of Minamoto no Yoshitsune and Ise Saburō Yoshimori, the first “ninjutsu manual” known as Yoshitsune-ryū Ninjutsu was written. While its contents are not yet fully separated from military strategy, the fact that ninjutsu emerged in a distinct, albeit incomplete, form from its foundation in the Kurama Eight Styles is noteworthy. Another significant development of this era is the clear emergence of ninja clans in Iga. The fully developed form of Yamabushi Heihō was being passed down to the local warrior families (Jizamurai or Dogō, local chieftains) of Iga and Kōga. From this period onward, Yamabushi Heihō began to gradually transform into what would be recognized as “ninjutsu.”

Ninjutsu in the Kamakura Period (1185-1333)

During the Kamakura period (1185–1333 CE), the introduction of Zen Buddhism, which rapidly spread among the samurai class, had a significant impact on the later development of ninjutsu—a point worth noting. In Iga and Kōga, the samurai groups that emerged internally, while operating in different environments, adopted a strict isolationist stance toward external forces. Internally, they began to advance their governance through a coalition of local chieftains (Dogō), employing a policy of direct military resistance against external enemies (through samurai unity) and a strategy of coexistence internally (balancing power among factions). It’s notable that the methods they adopted during the chaotic Sengoku period were already taking root at this time. Additionally, two key developments influenced the later evolution of Iga and Kōga ninjutsu: the Iga ninja clan leaders, the Hattori (and Momochi) clans, reconciled with the newly arrived Ōe clan (from Kawachi), extending their influence into Yamato and Kawachi; and the Kōga ninja clans came under the control of the Sasaki clan, the provincial protectors, establishing a communication route to Kyoto (Kyōraku).

Ninjutsu in the Nanbokuchō Period (1336-1392)

During the late Kamakura period (1185–1333 CE), amidst the turmoil surrounding the fall of the Hōjō regime, a military genius, Kusunoki Masashige, rose to prominence. Masashige emerged as a master of unconventional tactics (Kihenpō), the foundation of ninjutsu, completing the framework for both offensive and defensive unconventional strategies that had been initiated by Minamoto no Yoshitsune during the Genpei period. Additionally, he established an independent organization for espionage and stratagem, advocating for the necessity of intelligence and covert operations during peacetime—what he termed Dakkōnin (political ninjutsu)—within the field of military science (Heigaku). The ninjas of Iga and Kōga, alongside the Yamabushi, became a faction supporting the Southern Court through Masashige’s mediation.

Ninjutsu in the Sengoku Period (1467-1615)

The Sengoku period (1467–1615 CE) marks the era in which ninjutsu reached its full maturity. It is only in this period that we can finally encounter “complete” ninjutsu. During this time, “ninjutsu-like” practices emerged in various regions across the country, but apart from the ninjutsu of Iga and Kōga, no other form can be considered truly complete. In this sense, Iga and Kōga ninjutsu represents the pinnacle of Japanese ninjutsu, far surpassing the hastily developed, naturally occurring ninjutsu of other regions in terms of sophistication. This is precisely why Iga (and Kōga) ninjas were so highly valued during this period. It would not be an exaggeration to say that among the military commanders who best utilized ninjutsu, Tokugawa Ieyasu stands as the greatest and most significant. The influence of ninjutsu and ninja organizations in his rise to dominance cannot be overlooked. Another notable fact is the significant impact that the introduction of gunpowder had on Iga (and Kōga) ninjutsu during this period. Additionally, a key characteristic of this era is the emergence of distinct schools (Ryūha) in military science (Heigaku), martial arts (Bujutsu), and ninjutsu (Ninjutsu), with these disciplines developing a high degree of artisan-like specialization (Artisan-sei) while also becoming professionalized.

Ninjutsu During the Oda-Toyotomi Period (1568-1615)

The Oda-Toyotomi period (roughly 1568–1615 CE, spanning the reigns of Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi) was the era in which ninjutsu, perfected during the Sengoku period, flourished most vibrantly. As mentioned previously, Japan’s largest and most formidable ninjutsu organizations—Iga-ryū and Kōga-ryū—were almost exclusively under the control of Tokugawa Ieyasu during this time. Consequently, the history of ninjutsu in this period cannot be examined independently of Ieyasu’s policies and actions. The activities of ninjas during this era are directly tied to the establishment of the Tokugawa regime. This section explores the adversarial relationship between Iga and Kōga ninjas and Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi, focusing on the events surrounding the Tenshō Iga Rebellion (1579–1581 CE), which was a major cause of this enmity. It also examines the movements of Iga and Kōga ninjas during this period, their nationwide dispersal, the origins and evolution of the Iga Dōshin (a ninja unit) within the Tokugawa Shogunate, and the history of the shogunate’s ninja management system within Iga.

Ninjutsu During the Tokugawa Period (1603-1868)

Overview of Ninjutsu’s Decline. Up until the early Tokugawa period, ninjutsu reached its peak, but as the demands of the era shifted, it rapidly entered a period of decline. The techniques and organizations of ninjutsu began to disintegrate swiftly, transitioning from political espionage to judicial espionage. It was during this time that ninjutsu’s secret manuals started to emerge publicly—a natural phenomenon given the changing times. As the era of judicial espionage began, the rise of talented figures like Ōoka Echizen-no-Kami (Ōoka Tadasuke), who became the town magistrate, marked the entry of Kishū-ryū ninjas into the ranks of covert operatives. The Shimabara Rebellion Chronicle (Shimabararanki) serves as a valuable record, casting a faint light on ninjutsu during its extinction phase alongside the last of the ninjas.

Excerpt above about Ninjutsu History from the book Ninjutsu Sono Rekishi To Ninja by Heishichirō Okuse.

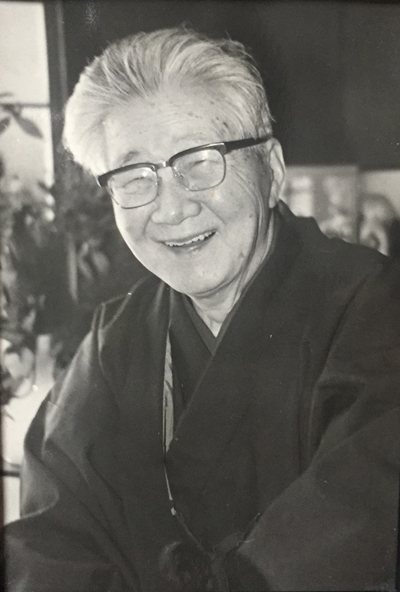

Heishichirō Okuse (奥瀬 平七郎, おくせ へいしちろう) was a Japanese novelist, researcher, and politician born on November 13, 1911, in Ueno, Japan. He passed away on April 10, 1997.

Okuse graduated from Waseda University and studied under the renowned author Masuji Ibuse. He developed a particular interest in ninjutsu (the art of stealth and espionage), contributing to its study and preservation. Professionally, he worked for the Manchurian Telephone & Telegraph Company.

In addition to his literary and research endeavors, Okuse served as the mayor of Ueno from 1969 to 1977. His multifaceted career reflects a deep engagement with both traditional Japanese martial arts and public service.