Ninja Jumping often need to escape by leaping over obstacles or walls, grabbing onto house eaves, or dodging sideways in the blink of an eye to hide from enemies. They may also have to jump across rivers too wide for pursuers or leap from low to high places to evade capture. When infiltrating enemy castles or houses, the ability to fly like a bird would render defenses and ambushes nearly irrelevant.

Ninja techniques include the Six Jumping Methods, encompassing six types of jumps:

- Forward Jump (Mae-tobi)

- Backward Jump (Ushiro-tobi)

- High Jump (Taka-tobi)

- Long Jump (Haba-tobi)

- Side Jump (Yoko-tobi)

- Diagonal Jump (Naname-tobi)

The standards are a high jump of 9 shaku (2.7 m), a long jump of 18 shaku (5.4 m), and a downward jump of 50 shaku (15 m). These figures likely represent ideal targets for ninja training. Beyond these, jumps were performed in pairs or trios or with tools.

忍びの跳躍訓練 Shinobi no Chōyaku Kunren (Ninja Jump Training)

To leap effectively, one must be light. Ninja regularly used slimming medicines made from wild coix seeds, ate tofu as a staple to maintain nutrition without gaining fat, and underwent rigorous, balanced daily training. This reduced excess fat, tightened muscles, and developed a flexible, resilient, steel-like physique.

During intense physical training, ninja reportedly wore deer leather undergarments. Sweating from vigorous movement wetted the leather, causing it to cling and constrict the body. Enduring this discomfort during training gradually slimmed the body and reduced sweating, as body odor could betray a ninja’s presence.

Jump training involved sowing hemp seeds in a plot of land and waiting for germination. Hemp grows rapidly, stretching taller daily. Ninja practiced jumping over it—forward, backward, sideways, and diagonally. Initially easy, the task grew harder as the hemp grew. Such training for about three years was necessary to become a competent ninja.

二人組人馬興業停止令 Futarigumi Jinba Kōgyō Teishi Rei (Two-Person Horseback Technique)

The term “ninba” (human horse) refers to a mid-Edo period spectacle, akin to modern circus acts, but I believe it originated as a ninja technique for leaping over high walls. Historical records claim it was devised in the Genroku era (1688–1704) for performances, but I suspect it’s older.

In Kyoto, a performer named Numa from Kinbuya Tabee, during the Genroku era, went to Edo, joined the equestrian Sasaki Heima’s school, and allegedly created the ninba technique inspired by equestrian skills. However, equestrianism and ninba share no technical similarities.

The Rakushu Genbun Taiheiki, Volume 4, mentions Sasaki Heima’s fame and ninba’s ability to astonish audiences. On July 24, Genbun 5 (1740), ninba performances were banned again. Though presented as derived from equestrianism, I believe destitute ninja, no longer receiving stipends, used their trained ninba skills in performances. Records show ninba was banned three times.

The Seihōroku, in an entry for April, Hōei 4 (1707), notes: “Recently, various acrobatics called ninba have gathered crowds, leading to imitators and potential misconduct, so ninba and other acrobatic performances are henceforth prohibited.” Another ban was issued in Genbun 5 (1740), and on May 11, Kanpō 2 (1742), the Asakusa-ji Diary records the dismantling of an acrobatics booth at Asakusa Temple due to concerns that “undesirable people learning and using it could lead to trouble.” The bans were issued because ninba could be misused by thieves if publicly displayed.

Was ninba such a shocking technique to warrant such scrutiny?

二人組人馬の技法 Futarigumi Jinba no Gihō (Two-Person Ninba Technique)

Jumping over a 10-meter-high wall or obstacle without tools is difficult, but with the two-person ninba technique, ninja could soar like birds (see frontispiece illustration).

One person stands with another on their shoulders, facing a high wall. For stability, the upper person places their feet on the lower’s shoulders, firmly grips the lower’s head, and crouches to avoid falling, timing the takeoff. The lower person holds the upper’s legs for stability. Both synchronize their breathing, sprint toward the wall or obstacle at tremendous speed, and at the optimal distance, the upper person kicks off the shoulders to leap, while the lower throws the upper’s legs upward. With the momentum of the sprint and elastic body movement, the black shadow arcs through the air like a projectile, clearing the obstacle.

For house infiltration, once one ninja lands inside, they throw a climbing rope outside, easily pulling the other over the wall (see illustration).

三人組人馬の技法 Sanningumi Jinba no Gihō (Three-Person Ninba Technique)

For obstacles over 10 meters that a two-person ninba cannot clear, a three-person technique is used. One person sits on a stone 4–5 meters from the obstacle, facing away, knees aligned horizontally. A second person stands naturally on the seated person’s back. The jumper starts a sprint from as far as 10 meters away, steps onto the seated person’s knees as a launch platform, and leaps upward. Just before, the seated person supports the jumper’s soles or thighs, and the standing person grips the jumper’s torso, all synchronizing to hurl the jumper high over the obstacle (see frontispiece illustration).

These flight techniques are most dangerous during landing, and until mastered, they reportedly cause frequent fractures, sprains, and bruises. I once saw the Soviet Russian Ballet perform a Cossack dance where dancers leaped high from the stage’s back, soaring over others to land at the front, using a method nearly identical to the three-person ninba. This technique likely originated in mainland China, spread north to the Cossacks, and eastward to Japan with ninjutsu. The claim it was devised from equestrianism in the Genroku era is likely a ninja cover story or jest.

Hop, Step, Jump

With a four-person team, jumping onto a 3–4-meter wall is simpler. One person leans against the wall, hands on it, head lowered, standing naturally. A second person firmly grasps the first’s waist, braces their feet, tilts their head right or left, and flattens their back. A third person hugs the second’s legs, crouches low, and flattens their back. The jumper sprints, using a triple-jump approach, stepping on the first, second, and third person’s backs, then leaping from the third to grab the wall’s edge (see frontispiece illustration).

Tool-Assisted Methods

Using a sturdy long board and a stone, create a seesaw. The jumper stands on one end, and another person jumps from their shoulders onto the raised end, launching the jumper over the wall. Pole vaulting with a spear or pole, or swinging across with a climbing rope like a pendulum, were also used.

This above about Ninja Jumping techniques was just one section translated from Japanese to English from the book…

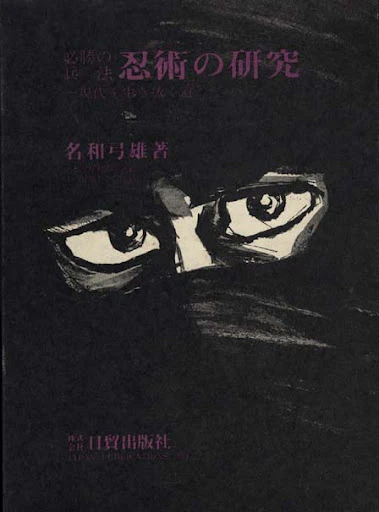

忍術の研究 Ninjutsu no Kenkyū by 名和弓推 Yumio Nawa

First published on November 1, 1972. It contains approximately 85,000 words across 377 pages, including around 50 pages of illustrations and index. The work explores historical ninjutsu, martial strategies, and their relevance to contemporary life.

About the Author

Yumio Nawa (real name: Sadatoshi Nawa) was born in 1912 (Meiji 45) into a samurai family of the Ogaki-Toda domain. He was the Sōke (headmaster) of Masaki-ryū Manrikigusari-jutsu and Edo Machikata Jitte-jutsu. His other works include A History of Torture and Punishment, Studies of Jitte and Hojō, and Weapons of the Shinobi, among others. He served as an executive director of the Society for the Research and Preservation of Japanese Armor and Arms, and a standing director of the Japan Writers Club. At the time of publication, he resided in Asagaya-Minami, Suginami Ward, Tokyo.