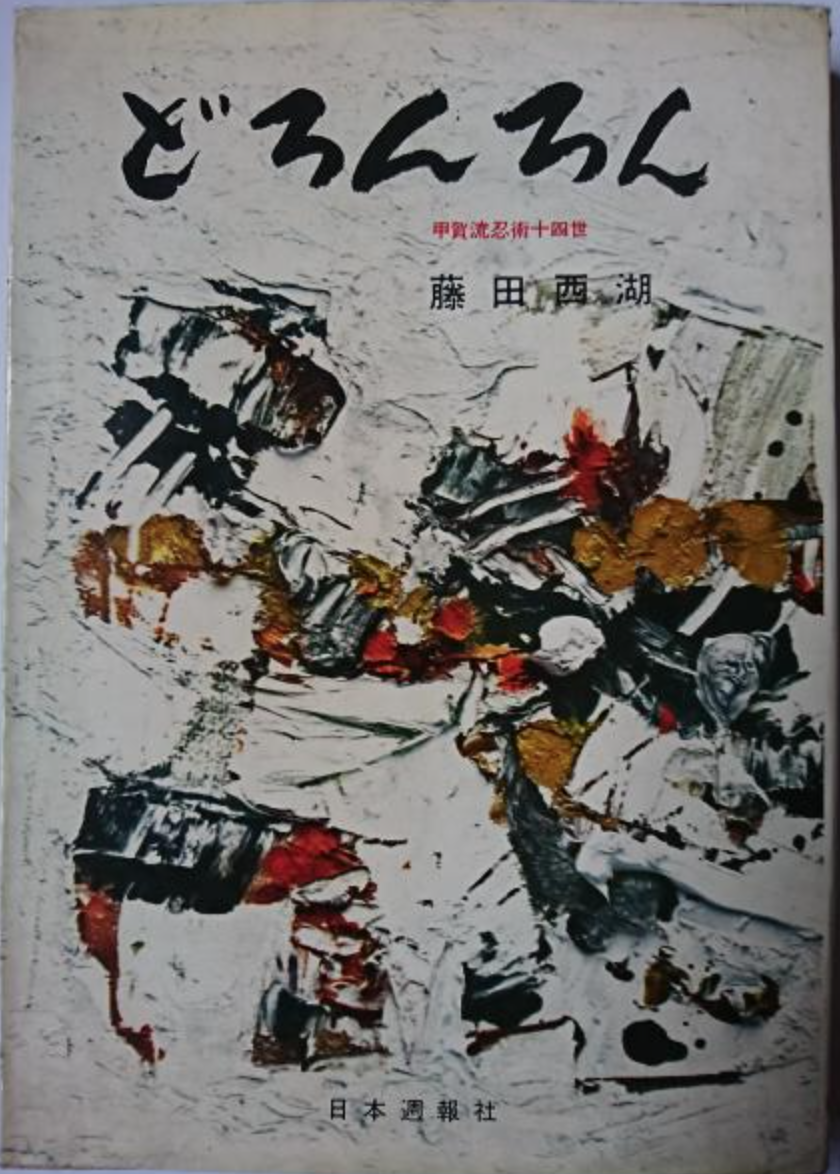

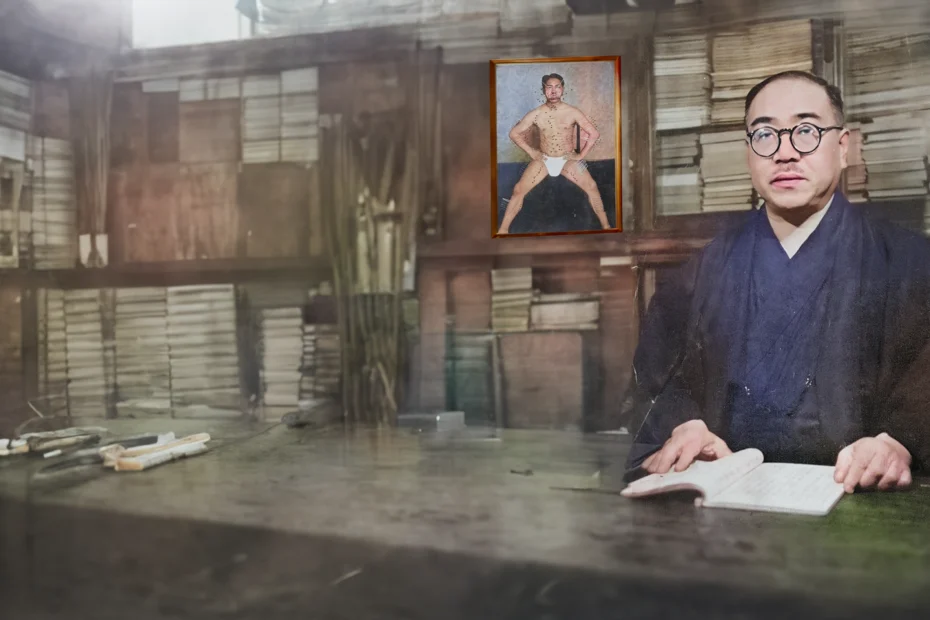

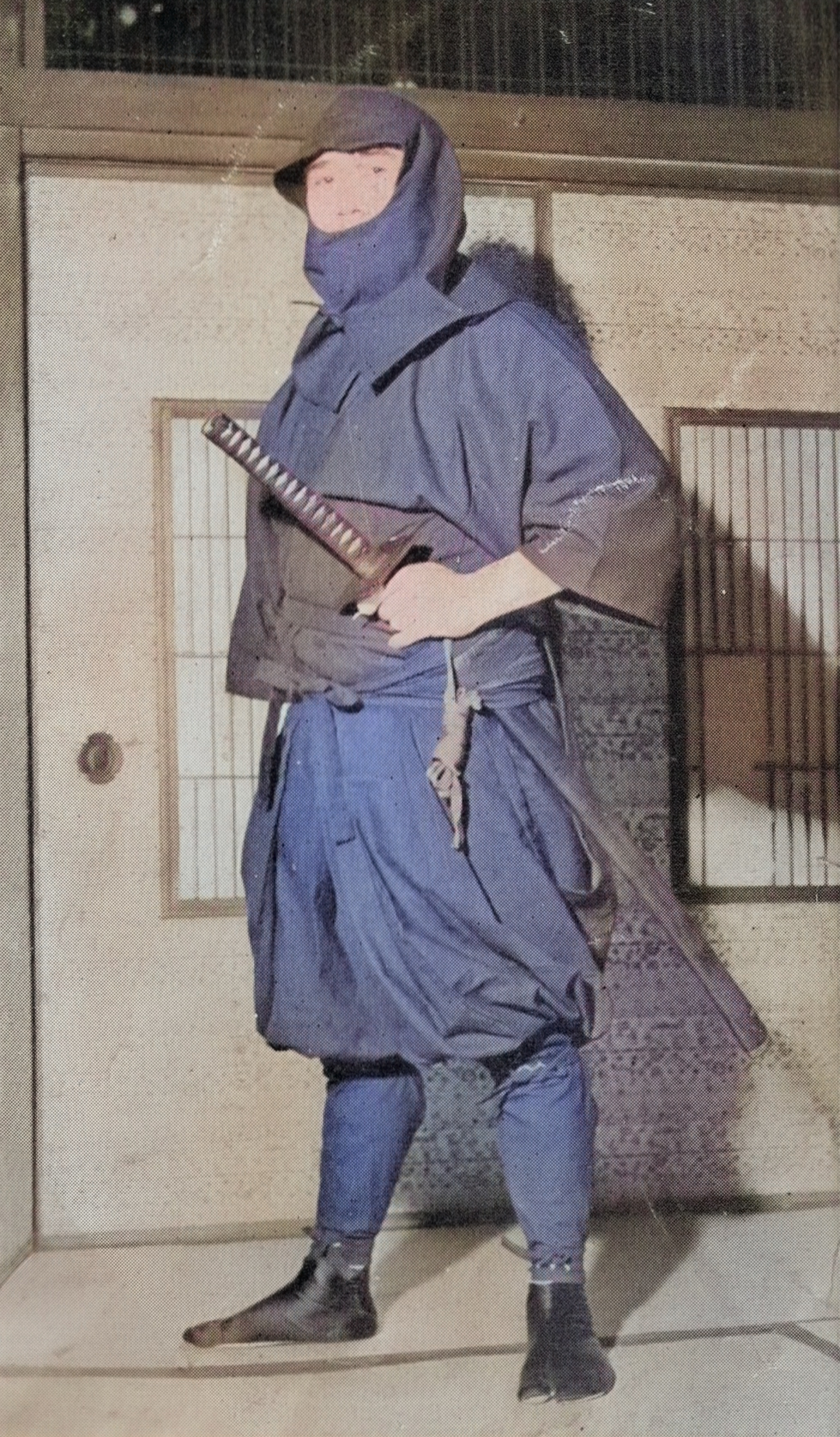

Fujita Seiko ninjutsu history about Fujita Seiko (藤田西湖) The Last Ninja, ninjutsu history, the 14th master of Koga-ryu (甲賀流) ninjutsu, is celebrated as Japan’s last true ninja. His autobiography, Doronron: The Last Ninja, offers a vivid account of his life, intertwining Fujita Seiko ninjutsu history with Japan’s evolving cultural and military landscape. This summary traces Seiko’s journey chronologically, from a fiery childhood to his role in wartime espionage and his post-war efforts to preserve ninjutsu.

A Rebellious Childhood and Early Influences (1899–1908)

Fujita Seiko ninjutsu history began on August 13, 1899, in Tokyo’s Asakusa district. Born Fujita Isamu, he was the second son of Morinosuke Hayata, a police detective renowned for capturing criminals like the infamous tailor Ginji. Seiko’s family had deep ties to the Tokugawa shogunate, serving as onmitsu (covert agents) for 300 years. This legacy set the stage for Seiko’s lifelong connection to ninjutsu, as his ancestors’ roles under Tokugawa Ieyasu relied heavily on espionage to maintain the shogunate’s stability.

Seiko’s childhood was marked by a fiery temperament. At six, he sought revenge for his brother’s bullying, attacking eleven older children with his father’s saber. “よし、おれが仇討ちに行つてやる” (Yoshi, ore ga adauchi ni itte yaru, “I’ll go take revenge!”), he declared, showcasing his boldness. This incident led to his temporary exile to Daiji Temple in Itsukaichi, where his rebellious streak continued. Seiko desecrated sacred statues in the temple’s Enma Hall, earning both punishment and a reputation as a troublemaker.

His early life was also shaped by tragedy. In 1905, Seiko nearly died from diphtheria, a near-death experience that left a lasting impact. His mother, Tori, revived him through sheer determination, forcing chopsticks wrapped in cotton down his throat to clear his airway. However, in 1908, on his ninth birthday, Tori succumbed to intestinal catarrh. “私は幼なごころにも悲しくて、毎日、裏山をみてはボンヤリ暮した” (Watashi wa osanagokoro ni mo kanashikute, mainichi, urayama o mite wa bonyari kurashita, “Even as a child, I was sad, spending each day staring blankly at the back mountain”), Seiko wrote, reflecting on his grief. This loss deepened his yearning for purpose, setting the stage for his immersion into ninjutsu.

Training in the Mountains and Koga-ryu Initiation (1908–1915)

After his mother’s death, Fujita Seiko ninjutsu history took a spiritual turn. At seven, Seiko followed a group of yamabushi (mountain ascetics) into the mountains, seeking solace and adventure. For over 100 days, he lived among them, learning survival techniques like cooking rice in a buried cloth and enduring harsh conditions. This experience, though not formal ninjutsu training, honed his resilience, a trait crucial to his later mastery of Koga-ryu.

At nine, Seiko returned home, where his grandfather, Shintazaemon—the 13th Koga-ryu master—began his formal ninjutsu training. “お前は見どころがあるから、これから忍術の稽古をつけてやろうと思うが、どうだ、やる気があるか” (Omae wa midokoro ga aru kara, korekara ninjutsu no keiko o tsukete yarō to omou ga, dō da, yaruki ga aru ka, “You have potential, so I’ll train you in ninjutsu—do you have the will to do it?”), Shintazaemon asked. Seiko eagerly agreed, sealing their bond with a ceremonial 金打 kanau (clash their swords’ tsuba (guards) together to make a vow).

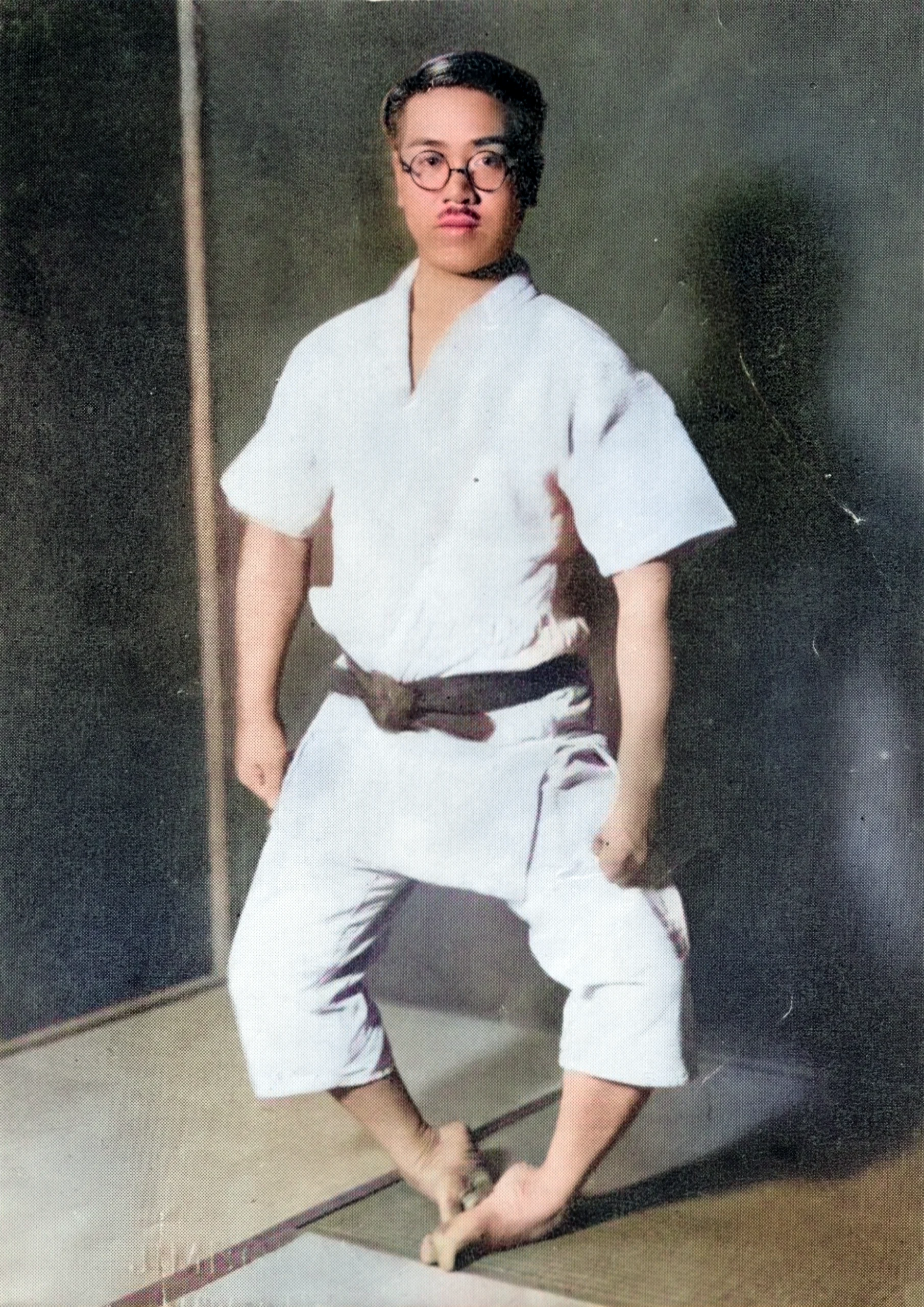

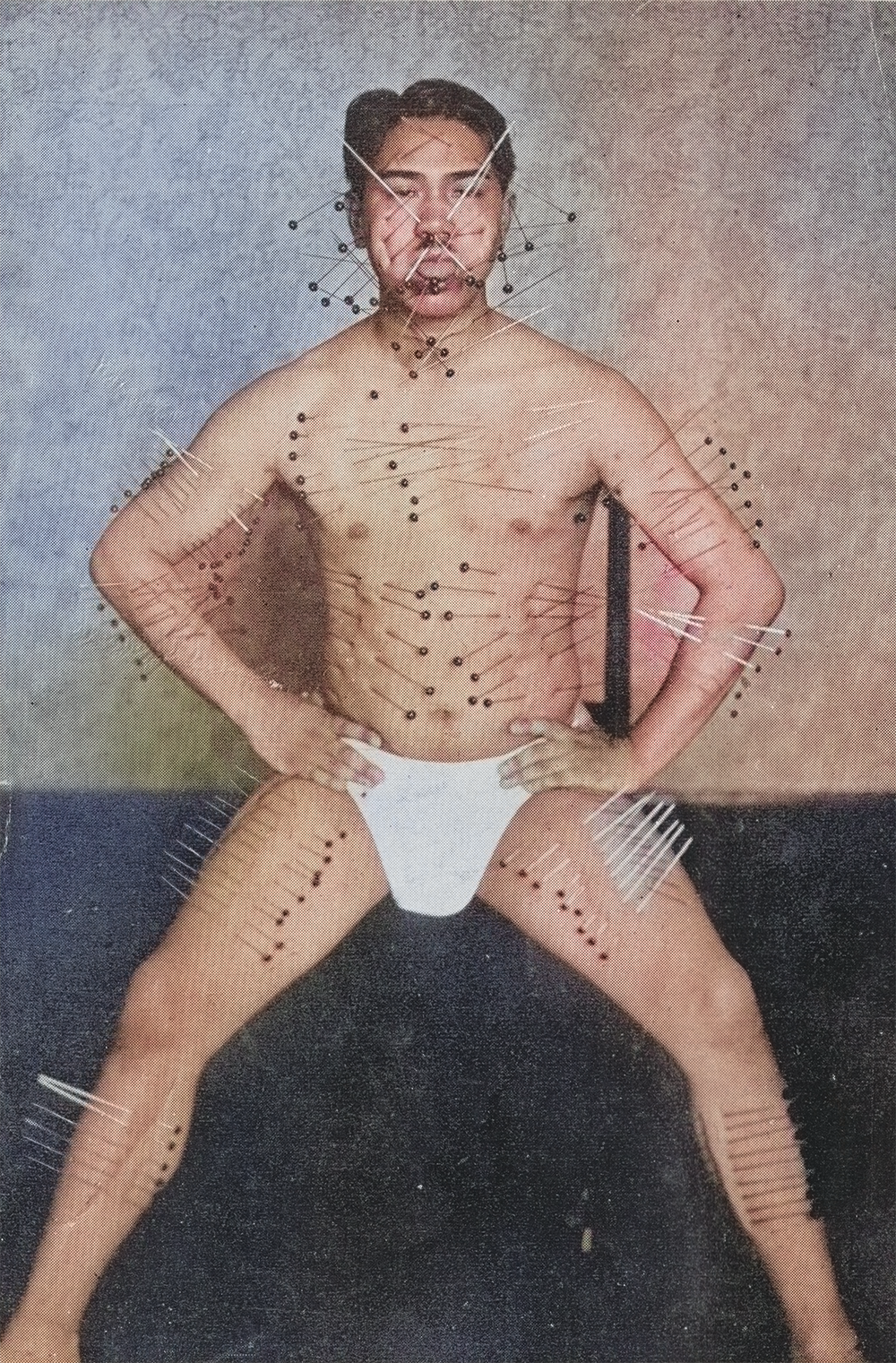

Seiko’s training was grueling. He practiced breathing techniques to remain undetected, attaching cotton to his lips to ensure silent respiration. He mastered tsumasaki aruki (tiptoe walking) to enhance stealth, enduring pain as he balanced on his toes for hours. He also strengthened his hands by thrusting them into sand, gravel, and clay, a practice that left his fingers bleeding but built formidable strength. These exercises were foundational to Fujita Seiko ninjutsu history, preparing him for the physical and mental demands of Koga-ryu.

A Ninja in a Modernizing Japan (1915–1930)

As Japan entered the Taishō era, Fujita Seiko ninjutsu history adapted to a changing world. In his teens, Seiko studied at universities like Waseda and Meiji but was expelled for his rebellious behavior. He eventually graduated from Nihon University’s religious studies program in 1919, balancing his education with journalism and martial arts instruction. These roles exposed him to modern ideas while keeping him rooted in ninjutsu traditions.

Seiko’s expertise in ninjutsu drew attention from military circles. He began teaching at institutions like the Army Toyama School, blending ancient ninja techniques with modern warfare. His skills in stealth, espionage, and survival made him a valuable asset, as Japan’s military ambitions grew. Seiko also explored esoteric practices, later documented in works like Shinshin no Maki – Jō, reflecting the spiritual depth of Fujita Seiko ninjutsu history.

During this period, Seiko inherited the title of 14th Koga-ryu master from his grandfather, a role that came with immense responsibility. He was one of the last keepers of a tradition that once boasted 53 Koga-ryu houses, a decline he attributed to the art’s secretive nature and rigorous demands. “忍術は、よほど克己心の強い者でなければ修業できない” (Ninjutsu wa, yohodo kokkishin no tsuyoi mono de nakereba shugyō dekinai, “Ninjutsu cannot be mastered without strong self-discipline”), he noted, highlighting why the art faded as Japan modernized.

Wartime Contributions and Disillusionment (1930–1945)

The Shōwa era brought Fujita Seiko ninjutsu history into the realm of warfare. During the Second Sino-Japanese War, Seiko traveled to occupied territories, using his skills to open safes and decipher codes. His ninjutsu expertise made him a key operative, often flying to China on urgent missions. As World War II escalated, he taught at Nakano School, training special forces in guerrilla tactics and psychological warfare.

Seiko’s wartime contributions extended beyond combat. He inspired troops with demonstrations like rope-escaping, symbolizing resilience. “日本は今、敵のためにガンジガラメになっているけれども、技術の鍛練と精神力によっては、この通り継も抜けられる” (Nihon wa ima, teki no tame ni ganjigarame ni natte iru keredomo, gijutsu no tanren to seishinryoku ni yotte wa, kono tōri nawa mo nukerareru, “Japan is now bound by the enemy, but with technical training and mental strength, you can escape ropes like this”), he told soldiers, boosting morale amid dire circumstances.

He also developed innovations like netsuryōgan (heat-retaining pills) for soldiers and Neo-Aochin, a stimulant later misused as Hiropon. However, Seiko grew disillusioned with military leaders’ self-interest, refusing honors to maintain his independence. “私は中将の前に出れば中将と友達づきあいに話したし、大将の前に出れば大将と同格に話した” (Watashi wa chūjō no mae ni dereba chūjō to tomodachi zukiai ni hanashita shi, taishō no mae ni dereba taishō to dōkaku ni hanashita, “I spoke to a lieutenant general as a friend, and to a general as an equal”), he wrote, emphasizing his refusal to bow to hierarchy.

Post-War Preservation and Legacy (1945–1958)

After Japan’s defeat in 1945, Fujita Seiko ninjutsu history faced new challenges. The GHQ banned martial arts, viewing them as militaristic, but Seiko used this time to preserve Japan’s traditions. He founded the Japan Martial Arts Research Institute, compiling Bujutsu Ryūmeiroku, which documented 4,420 martial arts styles, including 71 ninjutsu schools. His work ensured that Koga-ryu’s legacy would endure, even as he remained its last practitioner.

Seiko criticized the sensationalized depictions of ninjutsu in media, advocating for its scientific and spiritual depth. “忍術ほど科学的で進歩的なものはなく、しかも武芸百般を総合し、精神と肉体の練磨において、このくらい厳しいものはない” (Ninjutsu hodo kagakuteki de shinpoteki na mono wa naku, shikamo bugei hyappan o sōgō shi, seishin to nikutai no renma ni oite, kono kurai kibishii mono wa nai, “Nothing is as scientific and progressive as ninjutsu, encompassing all martial arts, with such strict mental and physical training”), he asserted, emphasizing its true nature.

In 1958, Seiko published Doronron, reflecting on his 50-year journey as a ninja. He feared ninjutsu’s extinction, noting, “わが国の正しい忍術の道統は、私を最後として絶えるものとみなければならない” (Waga kuni no tadashii ninjutsu no dōtō wa, watashi o saigo to shite taeru mono to minakereba naranai, “Our country’s true ninjutsu tradition must be seen as ending with me”). Without a successor, he aimed to leave a record for future scholars, ensuring Fujita Seiko ninjutsu history would inspire generations.

The Enduring Impact of Fujita Seiko Ninjutsu History

Fujita Seiko ninjutsu history is a bridge between Japan’s past and present. From a rebellious child to a wartime operative and post-war scholar, Seiko’s life reflects the resilience of Koga-ryu ninjutsu. His contributions—whether training soldiers, preserving martial arts, or challenging stereotypes—highlight the depth of this ancient art. Through Doronron, Seiko’s legacy endures, offering a profound glimpse into the world of Japan’s last ninja and the enduring relevance of Fujita Seiko ninjutsu history.

This above was a summarisation translated from Japanese to English from the book…

『どろんろん (Doronron)』 by 藤田西湖 Fujita Seikō

First published in September 1958 (Shōwa 33), this autobiographical work spans over 370 pages and provides a vivid and personal look into the life of Fujita Seikō, the 14th head of the Kōga-ryū school of ninjutsu. Through stories, historical accounts, and training descriptions, it captures the vanishing traditions of the shinobi, combining rigorous martial instruction with folklore and philosophical insight.

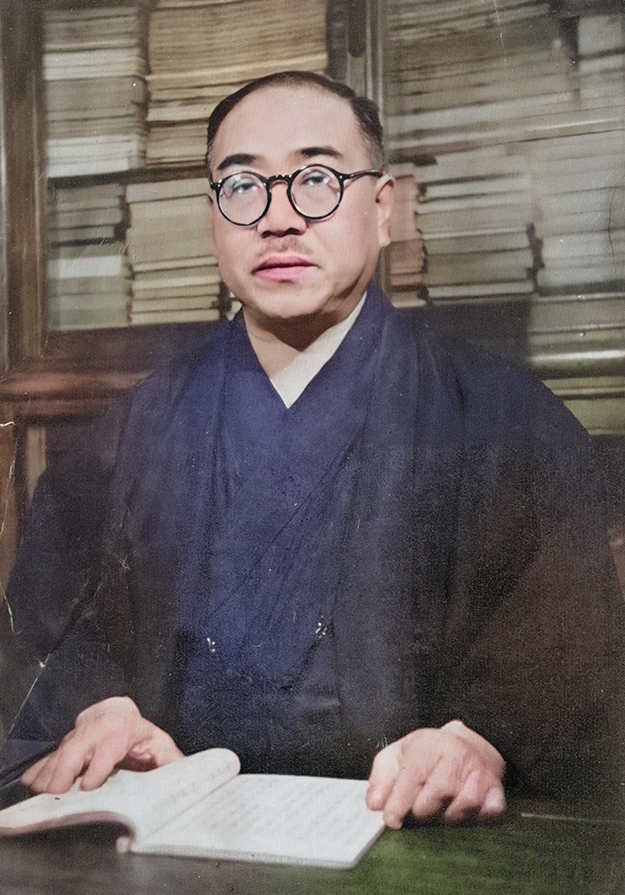

About the Author

Fujita Seikō (real name: Isamu Fujita) was born in 1898 and raised as the heir to the Kōga-ryū ninjutsu tradition. Known as the “Last Ninja,” he received his early training from his grandfather and continued his path through ascetic mountain practice and secret missions during wartime. In addition to his martial prowess, he became a widely known expert in yoga, mysticism, and traditional Japanese martial arts. He was famous for feats such as walking on the tops of his feet to impersonate the disabled, and for enduring extreme physical training. His works provide rare insights into practical ninjutsu and its survival into the modern era. He passed away in 1966.